Community Spotlight: Sharon Benmaman

Sharon Benmaman

Sharo n is Vice President of the Federation Board of Directors. She has also served Federation as Chair of the Central Budget Review Committee, which is responsible for the allocations process to our beneficiary agencies, and was Women’s Philanthropy Division Campaign Chair.

n is Vice President of the Federation Board of Directors. She has also served Federation as Chair of the Central Budget Review Committee, which is responsible for the allocations process to our beneficiary agencies, and was Women’s Philanthropy Division Campaign Chair.

Currently, she is also on the board of National Council of Jewish Women Minnesota. Professionally, Sharon does program and project managment consulting. She is married to John Allen and they have two sons in their 20's, Daniel and Michael. They live in Mendota Heights.

My Path to Spanish Citizenship by Sharon Benmaman, July 2020

In 2015, the Spanish government passed a law known as the Right of Return, allowing Sephardic Jews outside of Spain to apply for citizenship. The intent was to “right an historic wrong” and demonstrate that more than 500 years after the Inquisition began, Jews were once again welcome in Spain. I heard about the law when it passed but had not given it much thought. However, a 2016 trip to Spain and Morocco to trace my father’s life changed that.

My dad, Jose Benmaman, grew up in Tetuan, Morocco and moved to Spain at age 20 where he spent the next 17 years of his life. He studied pharmacy at the University of Madrid, but to be a pharmacist in Spain one had to be a citizen. During those years that meant being baptized, and as a devout Jew this was not an option for my dad. He had friends who even offered to get papers made up saying that he had been baptized but he wanted no part of it. So, my father was never a Spanish citizen.

My dad decided to pursue his doctorate instead, and it was then that he was added to the faculty, only the second Jew to teach at the University since the Inquisition when Jews were forced to convert to Catholicism or leave the country. Spain today has one of the smallest Jewish communities in the EU – fewer than 50,000, a fraction of the number who lived in the country before 1492.

I grew up hearing many stories about his years in Morocco and Spain. This trip in 2016 brought so many of his stories to life for me. Travelling the same streets as my father and recalling his stories about how he was nearly forced to leave the country more than once because he was not a citizen, I realized that I now had an opportunity that he never had. I decided I would apply for citizenship as a tribute to him.

Tracing my father's life

Unfortunately, my father passed away in 2013, so I was unable to share my experiences with him. While in Morocco we visited his hometown of Tetuan. When he lived there in the 1920’s and 30s, there were thousands of Jews but today only six remain. We visited the Jewish cemetery, which is the largest in Morocco with graves over 500 years old. After a long search, I was able to find the tombstones of my great grandparents.

Later, we visited the street where his family apartment was located. Although we didn’t know the exact location, we visited one of the apartments, and hidden inside the door frame was a pocket that once held a mezuzah. We don 't think this was his family home but like to think that he passed through this neighbor's door often when he lived there (and kissed the mezuzah!).

't think this was his family home but like to think that he passed through this neighbor's door often when he lived there (and kissed the mezuzah!).

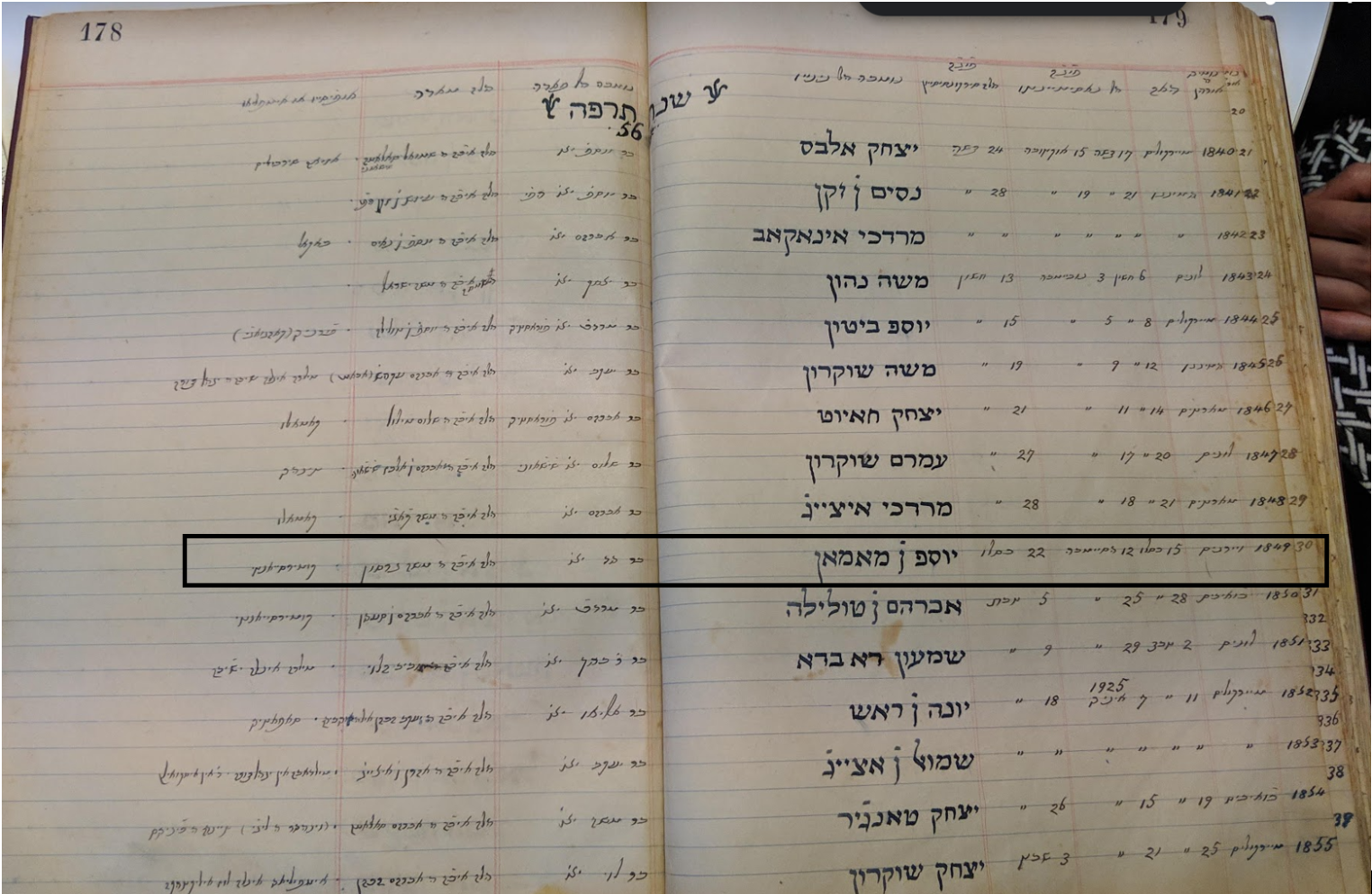

While in Madrid we had the opportunity to meet one of my father’s childhood friends, Pinhas. It was wonderful to hear stories about my father’s past. He told me about the Registry of Circumcisions that the mohel in Tetuan kept from 1881-1940. I was able to get a reproduction of the Registry that included a transcription of all of its entries. My father, grandfather, and uncles are all in it. On a subsequent trip to Spain, I was able to see the original that is housed at the Sephardic museum in Toledo.

Pinhas also told us about a statue in Buen Retiro park of Dr. Ángel Pulido Fernández (1852–1932), a big supporter of Sephardic Jews in the early 1900s. My father greatly admired Dr. Pulido; I remembered an article he wrote about him, and it had a picture of him with Dr. Pulido’s son at a statue dedication in 1954. We decided to go to the large city park and search for the statute, although we feared it might take hours to find. Fortunately, we found it right away and took a photo of me standing in the same spot where my dad posed for the dedication 62 years before.

Jose Benmaman (left), age 30, with son of Dr. Pulido, December 1954 at the statue dedication. Sharon Benmamn at the same spot, 62 years later.

The application process

When I made the decision to apply for Spanish citizenship, I discovered that the qualifications were cumbersome and the process incredibly time-consuming and expensive. Undoubtedly, many Sephardic Jews were discouraged by or unable to complete this process due to its burdensome requirements. At of the end of 2019 it was estimated that no more than 5,000 Sephardic Jews would be granted Spanish citizenship— one percent of the 500,000 that the Spanish government said would benefit from the law, and just 0.15 percent of the estimated 3.5 million Sephardic Jews in the world today. The law expired in October, 2019.

-

Proof of Sephardic heritage, including a letter from the Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain (this was actually the easiest part!)

-

Copy of my father's notarized birth certificate from Tetuan, Morocco

-

Certificate showing my Diploma for Spanish proficiency test. I had to fly to Chicago to take this because it is administered only by the Cervantes Institute (on behalf of Spain's Ministry of Education) in only a handful of places in the United States.

-

Certificate showing a passing score on the exam of constitutional and sociocultural knowledge of Spain, also administered by the Cervantes Institute (requiring yet another trip to Chicago)

-

Birth certificate (notarized, apostilled* and translated**)

-

FBI background check (notarized, apostilled and translated)

-

State of Minnesota background check (notarized, apostilled and translated)

-

Trip to Spain to meet with the government's notary (which I did in Nov 2018)

-

"Proof of special connection to Spain" - this included:

-

Copies of my father's Spanish ID cards

-

Letter from University of Madrid confirming that my father attended, taught and obtained his PhD there

-

Letter from BBVA Compass, a Spanish bank, showing that I have a Spanish bank account (notarized, apostilled and translated)

-

Letter showing donations to an organization that fosters programs that perpetuate Sephardic history, ideals, cultural and religious traditions (notarized, apostilled and translated)

-

College transcript showing I studied Spanish (notarized, apostilled and translated)

I still need to jump through a few more hoops - another FBI background check (notarized, apostilled and translated, of course!) and a visit to the consulate in Chicago to take an oath of fidelity to the King of Spain and obedience to its Constitution and laws.